Paradox of Progress

Initial Thoughts

Our first Creativity in Design class of the new term was extremely thought-provoking for me. I’m from Mumbai, India - one of the most densely populated cities in the world. I did my undergrad in Computer Engineering and I’ve fortunately had access to a lot of new technology growing up as part of the Gen Z or Zillennials, whichever group you put 2001-born kids in. So when the lecture started discussing smart cities, I recalled all the times I’d heard of them during my engineering years. It was obviously an idea that all my classmates loved and potentially wanted to work towards. Thinking of our own city as a technological beast with every little aspect of our lives connected and networked in order to provide much better service to us was wonderful. It felt futuristic! What could ever be wrong with this?

◆◆◆

When the citizens of a city don’t know how to fix and manage failed technology in the city, the technology dies and it brings down a part of the city with it. Jarah Moesch had one such encounter in Tanzania when she bought bracelets made out of PVC. This PVC was originally used for a water pipeline project to bring more water into that locality. When this complicated and expensive system stopped working, none of the locals knew how to fix it because the engineers who brought this with them had left already. All the expensive building material was just sawed off and sold in the end.

Smart cities involve networked technologies and their benefits but are these benefits actually available to all citizens? A city’s development - whether structural, technological or economic – can often overlook the needs of its marginalised communities. One of these development concepts, the smart city agenda - often championed by big tech corporations and global city leaders, tends to have a homogenised, top-down approach that fails to address the different needs and challenges of more marginalised communities. All of these little benefits are either for the companies inventing and instilling smart city technology, the city council or a (very small) section of people that can actually afford the benefits. This feels like watering just one part of a garden and expecting the entire garden to thrive and flourish. I came across two projects that aimed to address this exclusion on a global scale and while they cover a lot of ground, there is still a lot of work required for a practical implementation - especially in developing countries.

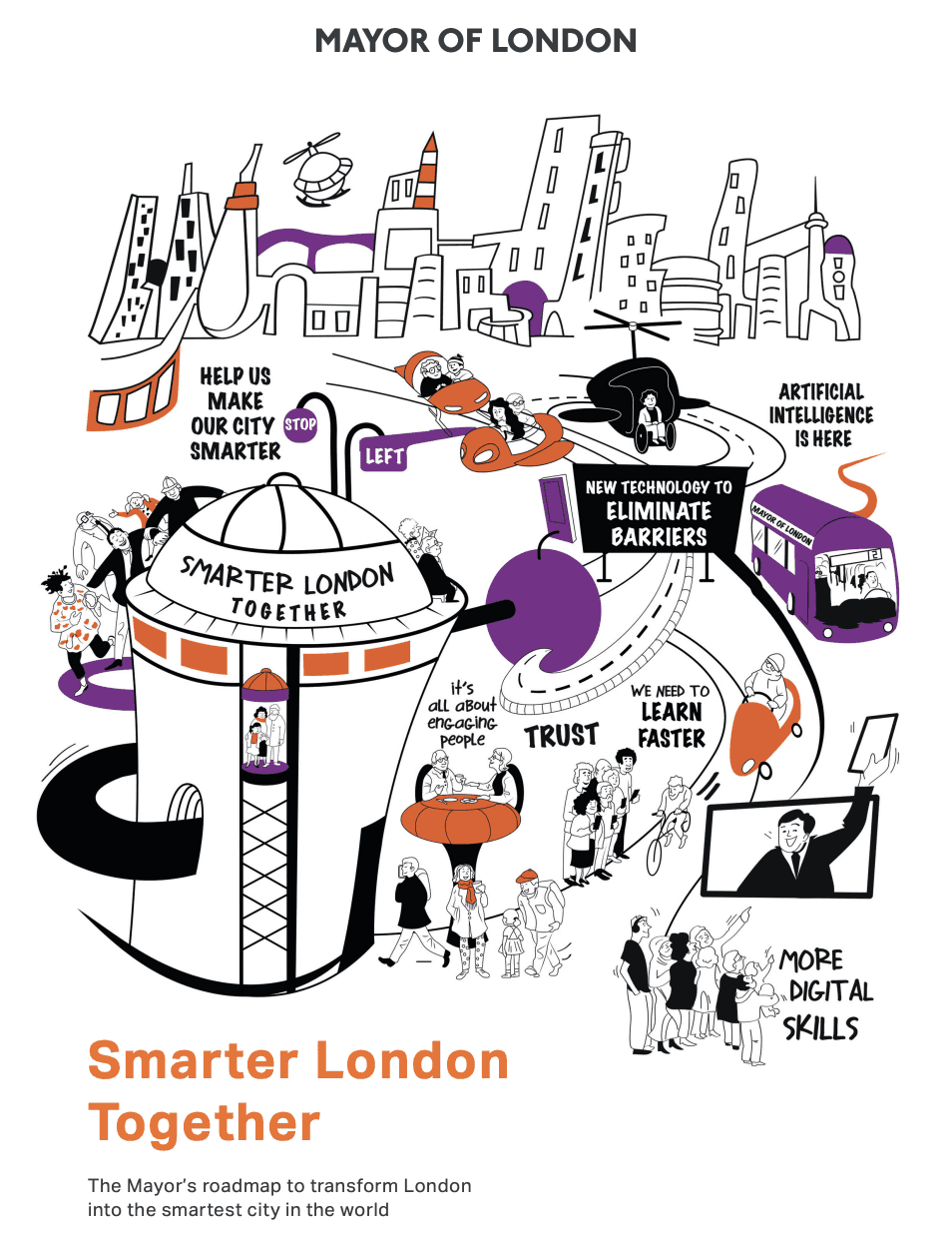

Quite a bit of research has gone into the “future-proofing” of smart cities. Talking about the UK specifically, the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology and Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport have curated a guidance collection consisting of 7 sections with the purpose of guiding security decisions and processes on the design, implementation and management of a connected place. This guidance was published in 2021 and has been regularly updated with research findings from smart city projects in Glasgow, Belfast, Birmingham, Bristol, Hull, Manchester, Milton Keynes, London and Peterborough.

While my newfound thoughts and opinions inspired by urban design methods might make me look like a skeptic of smart cities, I don’t think I’m completely against them either. I believe there is still a lot of promise in the vision if approached thoughtfully. I understand that this is where my current field of work, Human-Computer Interaction, can bring in that thoughtful approach. After all, it is the open-ended interaction between the user and the technology that the city depends on, right?